Somewhere there was brown paper and brown parcel tape. Somewhere in a cardboard box stacked underneath several other cardboard boxes there were these two things. Immediately to hand, however, was last years wrapping paper; red, patterned with white reindeer, snowflakes, birds and leaves. This was the paper the artist used to wrap the collage she was sending to the poet. The artist turned the paper inside out in an attempt to hide its unseasonal pattern, it was spring and she would rather have wrapped the collage in Crocuses and Tulips, not Reindeer. But the paper was thin, and Christmas peered out stubbornly through a smooth white fog.

The wintry Spring parcel arrived in North Vancouver two weeks later. A postman stood outside the poet’s house holding the package, staring fixedly at it, but not really seeing it because he was thinking back to 1998. Back then he was an easily embarrassed and much adored teenager. He was adored the most by his Aunt, who every year would knit him a special Christmas sweater. They were beautifully made and fitted well, but were always embellished with some goofy pattern or motif: kissing snowmen, dancing puddings, Santa with a bushy woolen beard. He’d always worn them when he went out, to make his Aunt happy, but when he reached nineteen and her latest creation sported a Christmas Trees adorned with real tinsel, snow fashioned from bits of lace, and a cluster of gold buttons in place of a star, he became less concerned with her happiness. He forced a smile when he opened it and wore it out begrudgingly. As soon as he was out of sight he took it off and turned it inside out, it looked unremarkable then; chunky-knit, beige, with threads of green wool forming an imperfect triangle. It was the last jumper his Aunt ever knitted him, he missed her.

It began to rain, and drops of water ran down the postman’s face onto the morning’s post. The poet, looking out of her window, saw people walking by with pale blue and red umbrellas, and she saw the postman, standing stock-still dripping with water. She went out to check that he was O.K and to fetch what he held in his hands into her white and warm and dry writing room.

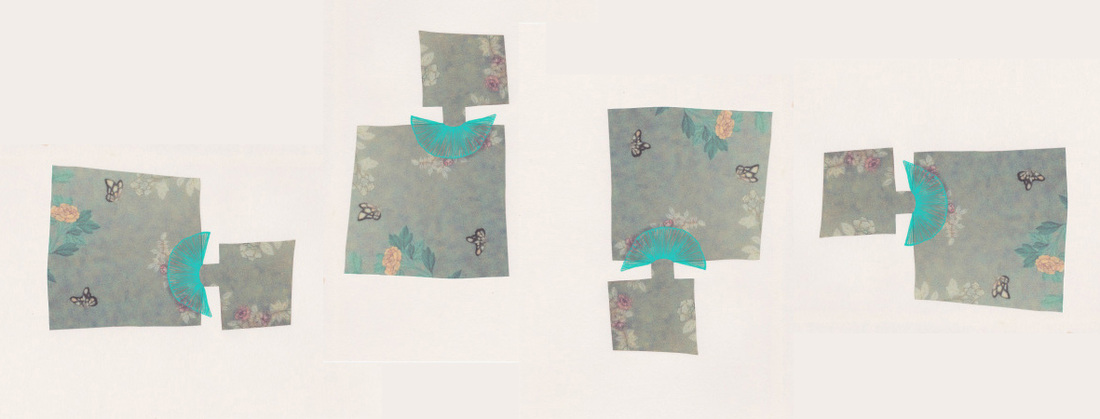

She held the unwrapped collage in her hands, and finding no indication of which way up it should be slowly turned it round and around. She saw a fragile and unnamed thing, possibly a figure with a vivacious neckline, or a detail from a map, a hesitant foot, or a ‘square’. This cut-out figure did something strange to her eyes, she couldn’t fix a scale to it. The butterflies and flowers had a depth of their own, the cut-out itself though looked flat, like it was made of wallpaper; something diminutive and domestic in contrast to the iridescent ‘collar’.

It was a thing that didn’t know what to call itself, and there was a freedom in that unnaming. The poet wondered what title could capture its energy without ‘capturing’ it?

“How about – ‘give keep can rigidity how picture open if direction foot’ ?” she wrote.

The wintry Spring parcel arrived in North Vancouver two weeks later. A postman stood outside the poet’s house holding the package, staring fixedly at it, but not really seeing it because he was thinking back to 1998. Back then he was an easily embarrassed and much adored teenager. He was adored the most by his Aunt, who every year would knit him a special Christmas sweater. They were beautifully made and fitted well, but were always embellished with some goofy pattern or motif: kissing snowmen, dancing puddings, Santa with a bushy woolen beard. He’d always worn them when he went out, to make his Aunt happy, but when he reached nineteen and her latest creation sported a Christmas Trees adorned with real tinsel, snow fashioned from bits of lace, and a cluster of gold buttons in place of a star, he became less concerned with her happiness. He forced a smile when he opened it and wore it out begrudgingly. As soon as he was out of sight he took it off and turned it inside out, it looked unremarkable then; chunky-knit, beige, with threads of green wool forming an imperfect triangle. It was the last jumper his Aunt ever knitted him, he missed her.

It began to rain, and drops of water ran down the postman’s face onto the morning’s post. The poet, looking out of her window, saw people walking by with pale blue and red umbrellas, and she saw the postman, standing stock-still dripping with water. She went out to check that he was O.K and to fetch what he held in his hands into her white and warm and dry writing room.

She held the unwrapped collage in her hands, and finding no indication of which way up it should be slowly turned it round and around. She saw a fragile and unnamed thing, possibly a figure with a vivacious neckline, or a detail from a map, a hesitant foot, or a ‘square’. This cut-out figure did something strange to her eyes, she couldn’t fix a scale to it. The butterflies and flowers had a depth of their own, the cut-out itself though looked flat, like it was made of wallpaper; something diminutive and domestic in contrast to the iridescent ‘collar’.

It was a thing that didn’t know what to call itself, and there was a freedom in that unnaming. The poet wondered what title could capture its energy without ‘capturing’ it?

“How about – ‘give keep can rigidity how picture open if direction foot’ ?” she wrote.